The Wisdom of the Serpent

Awakening Through Shakti or Ayahuasca — A Paradox for The Regenerative Age

The bus had already broken down. Twenty-some pilgrims were now piled into the back of a tractor, chugging its way down the road. The children who’d been chasing after us for the first few miles had long since disappeared into the horizon.

Then the tractor came to a halt.

“Cobra!” someone shouted.

We clambered off the trailer and stood in awe. There, in the middle of the road, sat a majestic king cobra with its hood raised high. A group of men had formed a semi-circle around it, sticks outstretched to ward off passing traffic. One man told us the snake had appeared at the same time every day that week.

Bowing to The Snake

Swami Nardinand, our 67-year-old guru, silently approached the cobra. He bowed. This was a man whose spiritual journey began before the age of five, entering deep meditative states for hours at a time while his parents lovingly unlocked his legs when they got stuck in lotus posture. At 14, with his mother’s blessing, he renounced worldly life and became a monk. Since then, he has lived and meditated under trees, in caves, and on riverbanks. And now here he was, lowering his head in reverence to a serpent in the middle of a dusty road on the way to the world’s largest gathering in human history.

Men tossed rupees beside the snake as an offering, petting it as if it were some kind of divine puppy. I’d never seen that level of veneration toward an animal—not even the sacred cows that roam the streets of India.

That serpent awakened something in me.

In this piece, I want to explore the deeper spiritual wisdom of the snake as revealed through two traditions that shaped our recent pilgrimage: the effortless Shaktipat lineage of the Vedic tradition, and the visionary medicine path of the Huni Kuin people of the Brazilian Amazon.

Jiboa: Guardians of the Rainforest

Weeks earlier, I sat in my first Ayahuasca ceremony led by Siriani Txana, a young Huni Kuin shaman from Acre, Brazil. She spoke often of the Jiboa, the great serpent spirit of the forest, protector and teacher, who first gifted his ancestors the sacred brew.

According to Huni Kuin oral tradition, one of their elders was taken by the Jiboa people—beings of the river and forest—who shared with him the vision and knowledge to create Ayahuasca. Other tribes, like the Shipibo, speak of being guided by plant spirits, or even other psychedelic plants, to find the right combinations. But for the Huni Kuin, it is the serpent who guards the gateway to divine knowledge.

Ayahuasca is brewed from two plants: the Banisteriopsis caapi vine and Psychotria viridis leaves. The latter contains DMT—the spirit molecule—and the former is a powerful MAO inhibitor. Without this precise pairing, the brew would be inert. Given the astronomical number of plant combinations in the Amazon, ethnobotanists like Dennis McKenna and Jeremy Narby have argued that discovering ayahuasca by trial and error would be statistically impossible—akin to tossing a box of toothpicks in the air and having them land as a chair.

Yet these peoples say it was not chance, but direct instruction—from the forest, from the spirits, from the serpent.

In ceremony, the serpent is not feared. It is revered. As the medicine takes hold and visions swirl into being, the Jiboa may appear—guiding, dancing, teaching. If a person taking medicine has a strong intention, the medicine can be an ally and a guide towards this outcome, similar to any technology, medicine is a vehicle for our deepest underlying motivations.

The Huni Kuin also speak of Kene, sacred geometric patterns that emerge in visions and adorn their art. These are not decorations. They are maps. Blueprints of the universe. Sacred codes. To drink the medicine is to commune with the intelligence of the rainforest—and to remember our place within it.

It is not about cultivating a blind faith in something outside ourselves. It is about a lived experience of the divine manifest in the world around us and in the world within us all.

Kundalini: The Serpent of Shakti

In the Vedic tradition, the serpent also lives within us.

She is called Kundalini, the coiled serpent energy at the base of the spine. Through the practice of Shaktipat, this divine feminine energy can be awakened by the blessing of a living master.

Swami Nardinand spoke of Samadhi, the state of pure consciousness where the observer and the observed become one. From this place, he transmits a blessing that activates Shakti within the Sadhak (practitioner).

And then?

“Just sit,” he says. “No effort. No technique. Just enjoy.”

One hour in the morning and one hour in the evening, the student is invited to do nothing but allow the grace of Shakti to work through them. There is no breath control, no mantras, no discipline in the traditional sense. Only surrender.

This is the paradox: that awakening does not require effort. It requires trust. Letting go. The Shakti energy rises like a serpent, clearing blockages, opening channels, leading the practitioner to deeper bliss and awareness.

This radically challenges conventional yogic paradigms of striving, austerity, and attainment. It reminds us that the divine is not achieved. It is inherent within.

In a similar way, this completely reframes our entire struggle with climate change. What if it’s not about creating solutions but rather recognizing nature has everything it already needs—we just need to learn how to stop destroying it?

Consciousness as technology

So much of the story progress over the last two hundred years has been driven by advancements and evolution in technology. We as children of the Eagle are obsessed with tools and with fire—the manifestation of the divine outside of us.

As we now cross the chasm of the polycrisis into whatever lies beyond, the invitation is to recognize the power of consciousness as the penultimate technology, as the steering wheel for all human activity.

In understanding the mythology and wisdom of various traditions around the world we can begin to recognize the vast array of tools that we have at our disposal to recognize ourselves as a part of nature and to begin to restore a lived experience of the sacred in everyday life.

Whether effortful or effortless, what if we perceived the internal path of awakening as integral to the regeneration of the earth as all the external forms?

Two Paths, One Mystery

One evening, in a shared conversation between Swami Nardinand and Siriani Txana, a question arose:

“What of working with medicine? Is it not a valid path to awakening?”

Swami responded with gentleness: “You are free to choose your path. I only offer what I have lived.”

He affirmed that the Shaktipat system is universal—beyond religion, tribe, or culture. A process to awaken what is already within, but asserted that the effortless path of awakening that requires no external inputs of medicine or any kind of practice is the fastest and most reliable way for any Sadakh.

Having sat in both worlds, I’ve come to respect the gifts and limitations of each. Psychedelics have offered me moments of stunning clarity and healing. But they can also provoke turbulence, distraction, and even longing. Sitting with Shakti can be restful and rejuvenating, but finding the motivation to sit for two hours everyday without ever glimpsing the infinite sea of bliss can be challenging.

Swami Ogananda once told me, “When we try to still the mind, it’s like trying to smooth ripples on water with our hands. We only make more waves. But if we let it be… it becomes still on its own.”

The medicine can show us the mountain. Shaktipat helps us live on it.

Together we have two faces of the divine feminine serving the awakening of humanity: Effortless and effortful—glimpsing the divine in nature and realizing the divine within.

Serpent as Symbol

Why, then, is the snake so often feared?

In the Abrahamic traditions, the serpent is cast as a villain. In Eden, it tempts Eve to eat the fruit of knowledge, claiming “You shall be as gods.” But if God made all things—including the serpent—was this not all part of the process? What if we needed to recognize ourselves as the universe experiencing itself in order to come into service of the web of life, as opposed to the ego hidden deep inside?

Perhaps the snake is not evil, but simply the bringer of awakening. Of duality. Of choice. To create or serve. To love or hate.

In the Amazon, the serpent is protector. In India, she is the divine mother.

In the West, the snake is often roadkill and nothing more. What a metaphor for the times we live in…

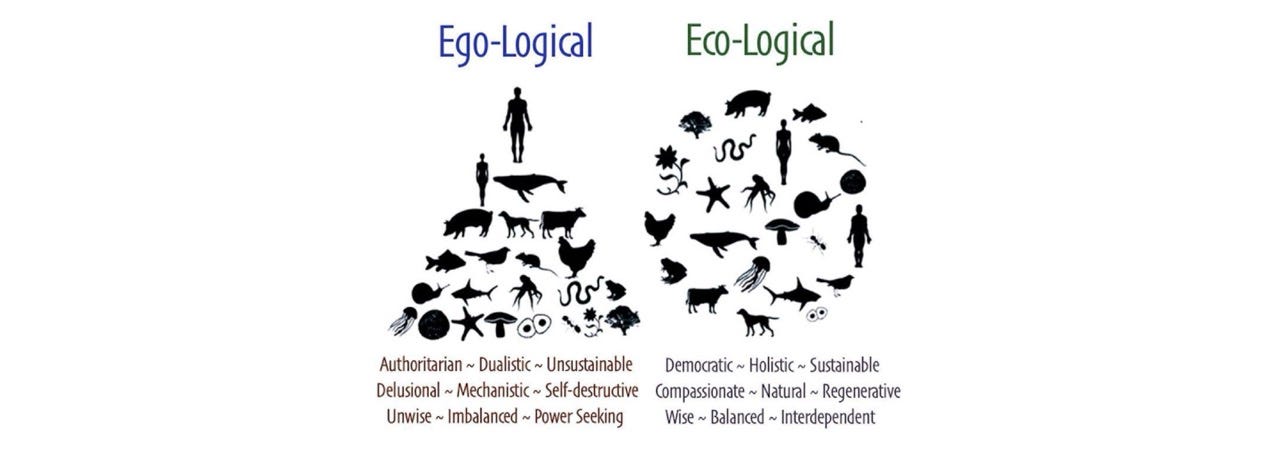

From Egological to Ecological

This moment in history seems to be spreading out like a forked tongue—one path leading to collapse, the other to regeneration.

We have used our intelligence to conquer nature. Now we must use it to commune with it.

The serpent, in both traditions, offers a living metaphor: shedding old skin. Coiling inward to remember. Striking only when necessary. Moving with grace.

The effortless path of Shakti teaches us to surrender to the living divine within. The medicine path of Ayahuasca teaches us how to witness the divine in the world around us. Both lead us back into harmony with nature, to the sacred web we are all woven into.

As leaders walking the path toward a more beautiful world, we must know when to dance and when to sit still. When to pause, and when to act. When to trust the flowing river and when break free to guide our own path with clear intention and resolved action.

This is the task of leadership in the regenerative age, to understand the wisdom of the beautiful tapestry of life around us and to act in concert with all living beings. It is about breaking free from the illusion of separation and recognizing ourselves as a part of nature.

It is about embodying the peace we hope to see in the world and emanating compassion in all that we do.

Dive deeper

If you’re keen to explore these themes at a deeper level, please do check out the trailer for our upcoming documentary Pilgrimage: Kumbh Mela, live now on Chuffed! We’re only $5k away from producing the full episode and going on the global festival circuit.

Reflections

If you are a leader walking the path of awakening, ask yourself:

What comes to mind when I think of a serpent?

How do I hold the paradox of effort and surrender?

What traditions have informed my leadership—consciously or unconsciously?

How am I integrating my insights into loving service?

May the serpent guide us not into fear, but into remembrance.

We are all here to belong.

This Earth is our only home.

What legacy will we leave for generations to come?