The Mineral Colonialism Powering Your ChatGPT, Google Search & Insta Feed

What Greenland, Venezuela, and a crypto “freedom city” reveal about the resource imperialism behind the AI boom

I’ve been tracking something that keeps me awake at night. Not the capabilities of AI—though those matter. Not the ethics of training data or alignment research. Something more fundamental: the physical infrastructure required to run these systems, and what we’re willing to do to secure it.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been pulling threads on Trump’s interest in acquiring Greenland, his administration’s moves on Venezuelan oil, and the quiet convergence of tech billionaires around Arctic mining projects.

What I found isn’t a conspiracy theory. It’s a supply chain strategy—one that connects the exponential energy demands of AI to a new form of resource imperialism that should concern anyone who cares about indigenous sovereignty, climate, or the future of regenerative economics. This is the story of how AI infrastructure is reshaping geopolitics, and what it means for those of us trying to build differently.

The electricity problem nobody’s talking about

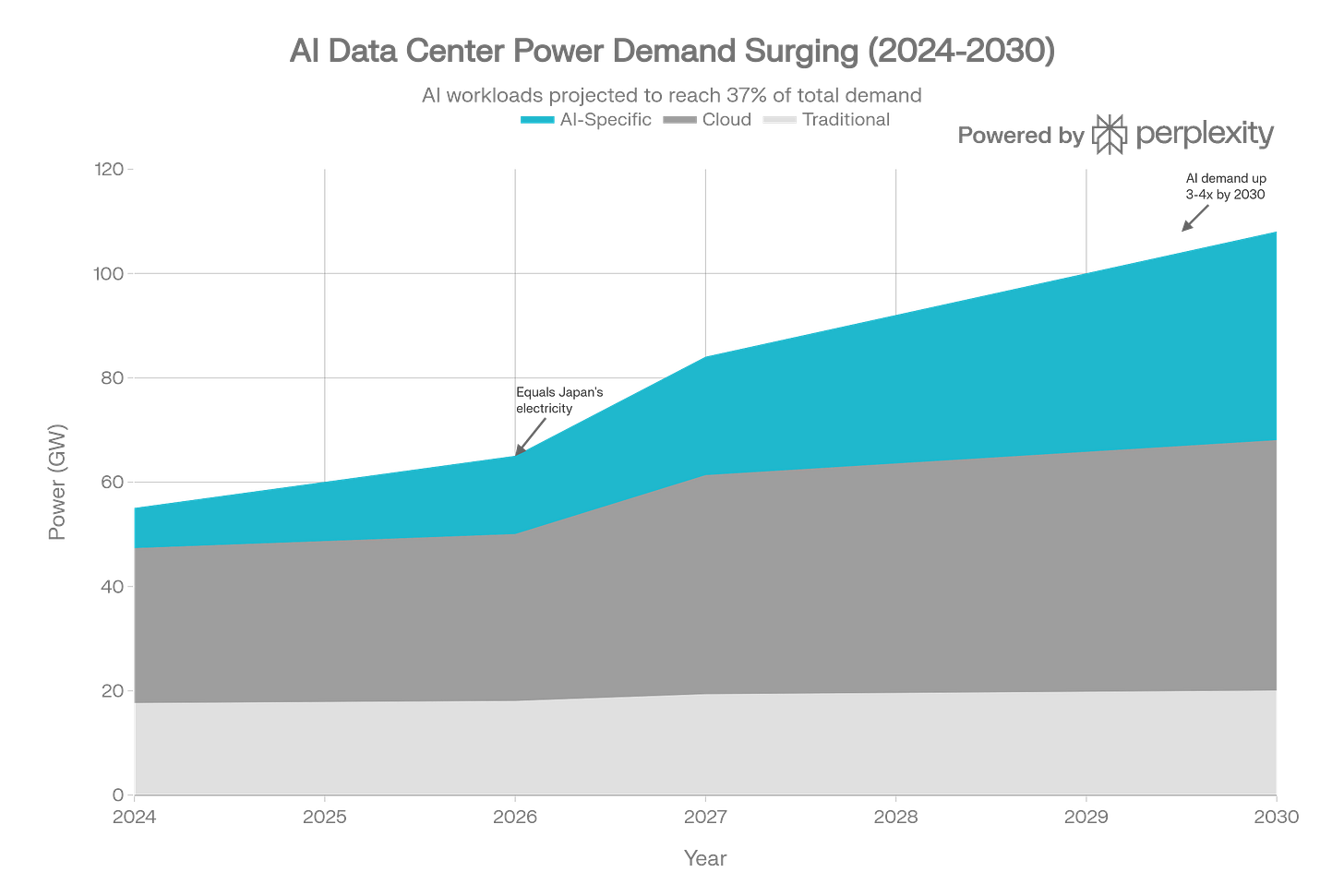

Let’s start with the hard constraint that drives everything else: power. Data centers currently consume about 1.1% of global electricity demand. By 2030, that figure is projected to reach 4%, with AI workloads growing from 14% of data center power draw to potentially 37-50%.

In absolute terms, AI-specific servers consumed 53-76 terawatt-hours in 2024 and are projected to consume 165-326 TWh by 2028—a 3 to 4-fold increase in four years.

This isn’t theoretical. In the United States, data centers already consumed 4.4% of national electricity in 2024. Household electricity bills have begun climbing; consumers in New Jersey, Ohio, and other states saw increases of $20-$30 per month directly attributable to data center power demands. A single large-scale AI training operation consumes as much electricity as a small city. The current trajectory means the US will exhaust available grid capacity within 2-3 years unless new generation sources are deployed at scale. This is the context for understanding what’s really happening with Venezuela.

Venezuelan oil for AI data centers

On January 3, 2026, Trump announced that the US would “take control” of Venezuela’s oil reserves—the largest in the world at 303 billion barrels, representing roughly 20% of global reserves. While framed as democracy promotion, Trump clarified the actual motive immediately: access to oil.

The timing isn’t coincidental. As the New Statesman analyzed: without some kind of energy breakthrough, the US faces growing social conflict between AI companies and regular households, political turmoil, and the prospect of losing the AI race to China. Venezuela’s oil, combined with new US-based renewable and natural gas infrastructure, is intended to power the multi-trillion-dollar data center buildout that will determine whether the US or China dominates the next decade of AI. But energy is only half the equation. The other half is minerals.

Greenland: the lynchpin of AI’s mineral supply chain

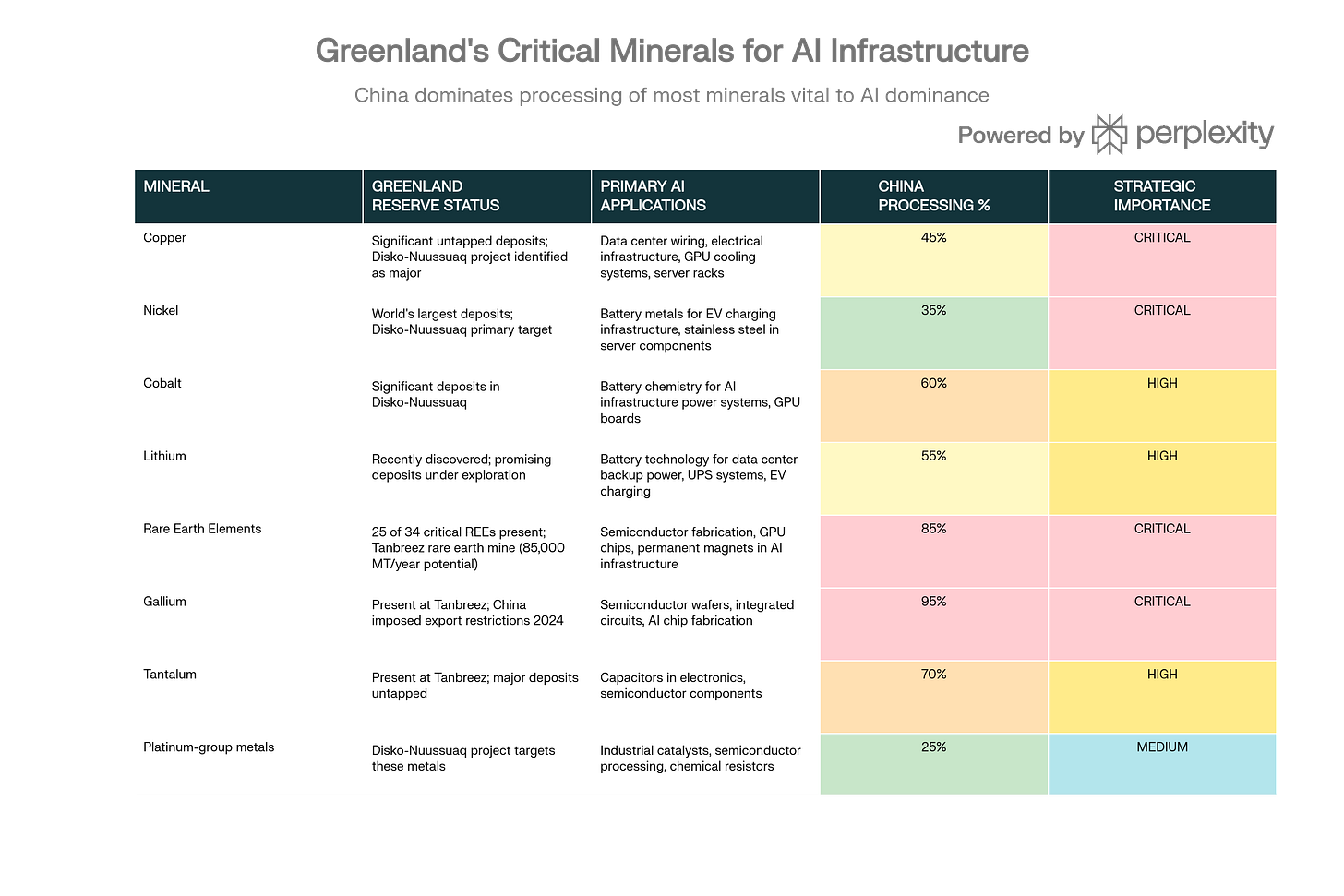

Greenland holds 25 of 34 minerals classified by the European Commission as “critical raw materials”—resources essential to the green energy transition but with high risk of supply chain disruption. Specifically, Greenland contains some of the world’s largest untapped deposits of nickel, copper, cobalt, lithium, rare earth elements, gallium, tantalum, and platinum-group metals.

These minerals are indispensable to semiconductor fabrication, battery technology, GPU chip design, and data center infrastructure. Collectively, Greenland’s mineral reserves are estimated to rival those of the entire United States. The problem is China’s chokehold on processing. While the US could extract minerals from Greenland, China dominates global processing: 85-95% of rare earth processing, 70% of tantalum, 60% of cobalt, 55% of lithium, and 45% of copper. This processing dominance gives Beijing leverage over US semiconductor supply chains and, by extension, over AI hardware production.

The billionaire positioning

The investors who recognized this vulnerability have positioned themselves to exploit it. Since 2019, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, and Michael Bloomberg have invested in KoBold Metals, an AI-driven mineral exploration company founded on the premise of using machine learning to locate and extract critical minerals. In their most recent funding round, KoBold raised $537 million, bringing their total funding to over $1 billion and their valuation to $2.96 billion.

Sam Altman, Marc Andreessen, and other Silicon Valley venture capitalists are also investors. KoBold’s primary focus is Greenland. The company holds a 51% stake in the Disko-Nuussuaq project, a 2,897 km² exploration license in southwest Greenland expected to yield some of the world’s largest deposits of nickel, copper, cobalt, and platinum-group metals.

Separately, the Trump administration has been negotiating with Critical Metals Corp for a stake in their Tanbreez rare earth mine—Greenland’s largest rare earth project. In October 2025, officials discussed a $120 million Export-Import Bank loan to accelerate the project. Tanbreez is projected to produce 85,000 metric tons per year of rare earth concentrate, along with gallium and tantalum.

The “freedom city” and regulatory arbitrage

Here’s where it gets strange—and revealing. Praxis is a venture-backed “network state” aiming to build a crypto-native “freedom city” in Greenland. Co-founded by Dryden Brown and Charlie Callinan, it’s backed by Peter Thiel (via his Pronomos Capital venture fund), crypto investors (Paradigm Operations, Arch Lending, GEM Digital), and other libertarian venture capitalists. In October 2024, Praxis announced $525 million in milestone-based funding.

The ideological framing is Thiel’s long-standing libertarian vision: create jurisdictions where wealthy individuals and tech entrepreneurs can escape taxation, regulation, and democratic accountability. But within the broader Greenland strategy, Praxis serves a more instrumental function: it provides a territorial sovereignty narrative for resource extraction.

If Greenland achieves de facto independence, and Praxis establishes a “freedom city” there as a logistics hub and compute center, then mineral extraction, processing, and crypto-based finance can be conducted in a jurisdiction effectively outside US regulatory oversight while remaining within the US geopolitical sphere.

In early 2024, Praxis co-founder Dryden Brown traveled to Greenland and met with members of parliament, arguing for Greenlandic independence backed by Praxis’s capital. More significantly, Trump’s appointment of Ken Howery—a longtime Thiel associate—as ambassador to Denmark creates a political channel through which this vision could gain traction. The ideological veneer of “freedom” and “network state” obscures what is fundamentally a strategy to extract Greenland’s resources under a sovereignty framework that bypasses democratic accountability, environmental regulation, and indigenous Inuit consultation.

The vertically integrated supply chain

These initiatives form a vertically integrated supply chain that, if executed, would allow the US AI oligarchy to bypass Chinese chokepoints and create an AI infrastructure ecosystem under their exclusive control:

Extraction (Greenland): KoBold and Critical Metals extract nickel, copper, cobalt, rare earths, gallium from Greenlandic deposits.

2. Processing (Friendshored): New US government initiatives fund alternative processing capacity in allied nations to break Chinese dominance.

Manufacturing (Taiwan + Arizona): TSMC—which controls 56% of advanced semiconductor foundry capacity and produces the majority of AI chips—manufactures GPUs using these minerals. TSMC is building massive facilities in Arizona with $165 billion in planned capex through 2030.

Energy (Venezuela + US renewables): Venezuelan oil, combined with US natural gas and renewable infrastructure, powers the data centers that run AI workloads.

Sovereign Compute (Praxis/Greenland): A crypto-native, minimally regulated compute hub serves as a logistics nexus for AI infrastructure deployment outside traditional US regulatory frameworks. Nvidia, which controls 95% of the AI GPU market and sits at the apex of the supply chain, directly benefits from this entire ecosystem.

This strategy faces significant structural obstacles—and here’s where I find hope. Greenlandic sovereignty and indigenous resistance Greenland’s 57,000 inhabitants are deeply opposed to foreign control and resource extraction driven by external interests. In 2021, the left-wing party Inuit Ataqatigiit won power explicitly on an anti-mining platform, opposing a rare earth uranium mine and banning all future oil and gas exploration.

The party’s leader, Múte Bourup Egede—the youngest prime minister in Greenlandic history—has stated unambiguously: “We do not want to be Americans.” Greenlandic environmental organizations and indigenous Inuit communities point to the legacy of past mining projects: the Black Angel lead-zinc mine (1973-1990) contaminated fishing areas that remain unsafe decades later, while the Cryolite mine left dangerous lead levels in fjords. Infrastructure reality Venezuela’s oil infrastructure is severely degraded. PDVSA estimates $58 billion in investment is needed merely to restore pipelines to mid-20th century efficiency.

Even with aggressive investment, it will take years—not months—to restore Venezuelan oil production to levels necessary for major data center expansion. Similarly, mining in Greenland is logistically and geologically difficult. Arctic conditions, supply chain vulnerabilities, and the need for new processing infrastructure mean that even optimistic timelines project 5-7 years before Greenlandic minerals reach meaningful scale in US supply chains.

Environmental and climate costs

The entire strategy brackets off climate implications. Extracting, processing, and transporting hundreds of millions of tons of minerals will generate substantial carbon emissions and environmental damage—the opposite of the claimed “green energy transition” that minerals are supposed to enable. Building new fossil fuel infrastructure in Venezuela to power AI data centers is antithetical to climate commitments and will accelerate the very crisis that makes Greenland’s melting ice sheets accessible for mining in the first place.

What this means for regenerative builders

I’m sharing this research because I believe those of us working on regenerative solutions need to understand the larger context in which we’re operating. AI is no longer simply a technological competition; it has become a driver of resource imperialism.

The computational power required to train and run large language models has become so enormous that it now competes for resources—energy, minerals, processing capacity—in ways that reshape geopolitical and economic relationships. The billionaires and their administration allies are deploying all the tools of 20th-century imperialism—territorial acquisition, control of energy resources, supply chain manipulation, quasi-sovereign jurisdictions—not for traditional colonial exploitation, but to ensure that the US AI oligarchy can monopolize the computational infrastructure that will define the coming decades.

From Beijing’s perspective, this is an energy and resource blockade. From Washington’s perspective, it is national security imperative. From Greenland’s perspective, it is a threat to sovereignty and autonomy. And from a global climate perspective, it represents a doubling down on fossil fuels to power a technology that is itself driving exponential energy consumption.

The question I keep asking myself

What does it mean to build with AI tools while knowing their physical infrastructure depends on these dynamics? I don’t have a clean answer. I’m using Claude to write code, using AI to accelerate my work, teaching others to do the same through Vibrana. And yet I’m also deeply uncomfortable with the supply chain violence that underlies the hardware I depend on.

Maybe the answer is transparency—understanding what we’re building on, naming it clearly, and working toward alternatives. Maybe it’s building tools that reduce computational intensity rather than assuming infinite scaling.

Maybe it’s supporting Greenlandic sovereignty movements and indigenous resistance to extraction. What I know is that the regenerative future we’re building can’t be founded on mineral colonialism and fossil fuel extraction. If AI is to be part of that future, we need to be honest about its current foundations—and work actively to change them.

These conversations matter and I’d love to have them with more builders in the space who are conscious about the environmental implications of AI and want to do something about it. If there’s interest, I can do a follow-up deep dive about the emerging hardware solutions that are reducing the energy and water consumption of data centers along with strategies for training AI models in a much more efficient way.

As they say if there is a will there is a way, and half of the job is realizing there’s a problem and deciding to do something about it! I’ve been coking up a ‘tree-MCP’ which plants trees throughout my day as I vibe code, if there’s interest in this I’d happily knock it up and ship on a weekend!

The world is definitely navigating through some wild times right now and I’m hopeful that those reading are able to find comfort in the present moment, either with friends or loved ones or in the beauty of nature.

Peace be with you 🙏

Data Sources & Further Reading