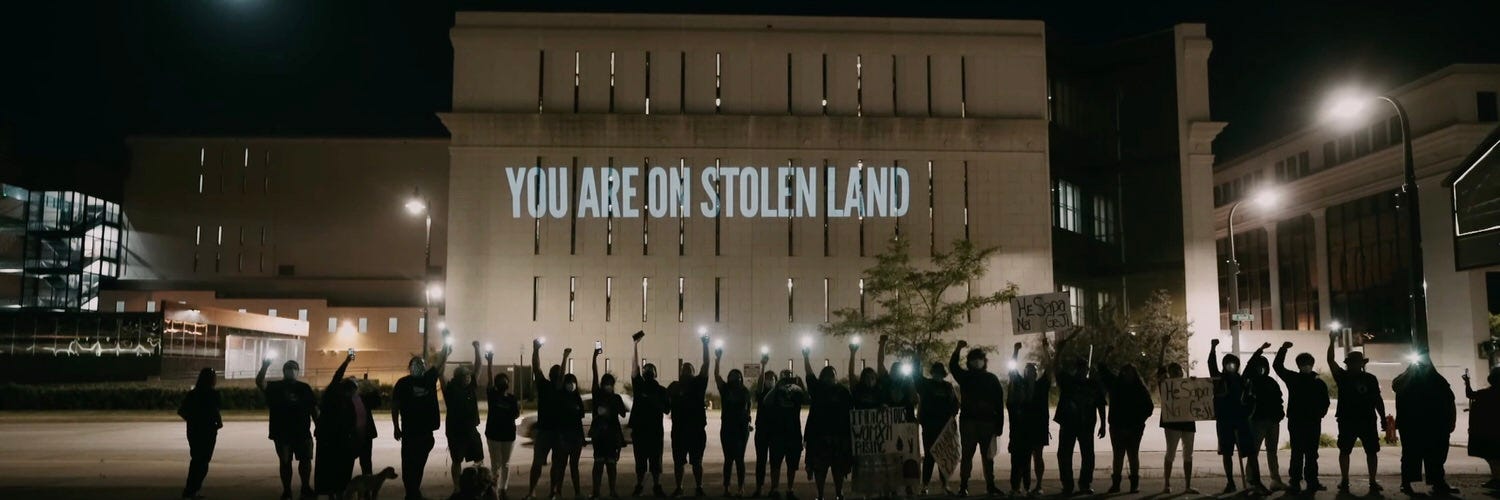

Since the 2015 Paris Agreement, we’ve invested trillions in decarbonization, clean technology, and net-zero ambitions. Yet climate chaos intensifies, biodiversity continues to collapse, and ecosystems are degrading faster than ever. Clearly, our prevailing strategies aren't working. We urgently need a deeper shift—a movement grounded in reconciling a profound truth: Western civilization was built on stolen land and the blood of innocent people.

The "Land Back" movement advocates returning land to Indigenous communities in the spirit of both social justice and ecological regeneration. While seemingly obvious, this movement requires not only external restoration of land ownership but an internal reconciliation of identity—a journey home to an authentic self free from the constructs of colonization. It challenges us to inventory land stolen by our ancestors and restore stewardship to original peoples, while simultaneously mapping the internal landscape of our identities, power structures, and notions of progress.

This ‘inside-out’ approach to systems change positions the Land Back movement as an essential missing link needed to stabilize our climate and restore societal and ecological balance. Indigenous stewardship delivers proven planetary benefits—reviving ecosystems, enhancing biodiversity, and mitigating climate change—and also offers profound opportunities to reimagine our education systems, justice systems, healthcare institutions, and how we care for the vulnerable among us.

The harsh reality is that the colonial approach to civilization has produced grave consequences for people and the planet. If we want to dream for the seventh generation we need to look back at the only communities who have proven they can live life sustainably on a land base for generations.

Historical Origins and Global Momentum

The struggle to reclaim Indigenous lands has persisted since colonization began, but the modern "Land Back" movement gained prominence around 2018. Key events like the 2020 Lakota protest at Mount Rushmore brought global attention, demanding the return of the sacred Black Hills and highlighting broader issues linking ecological stewardship, cultural revival, and political autonomy.

Examples worldwide illustrate growing momentum and the necessity for bridges to be built between indigenous communities and advocates of climate justice across society, from business owners, land owners, legal professionals, and social justice workers. This is not a battle that can be won without significant organization and coordination across the apparent boundary lines that colonial systems have used to divide us.

The Wiyot Tribe regained sacred Duluwat Island in 2019 after decades of advocacy, marking a historic voluntary return by Eureka city officials. Similarly, Minnesota’s Upper Sioux Community reclaimed ancestral territory in 2023, symbolizing reconciliation and ecological revival after 160 years of forced separation.

Indigenous Ecological Stewardship

Indigenous peoples, representing less than 5% of the global population, protect roughly 80% of the world’s biodiversity. Their territories exhibit significantly lower deforestation rates compared to surrounding areas. Over the past three decades, Indigenous-managed Amazon territories accounted for just 1.6% of regional deforestation, highlighting their stewardship efficacy.

Indigenous ecological practices integrate deep ecological knowledge, cultural traditions, and reciprocal relationships with nature. Australian Aboriginal traditional fire management reduces catastrophic wildfires and revitalizes ecosystems, while collective Indigenous governance in Brazil’s Amazon protects vast forest areas from industrial encroachment.

Reclaiming our own inner wisdom

This ecological wisdom parallels the internal wisdom each individual must reclaim—the intuitive knowledge and relational understanding suppressed by colonization. Both external land restoration and internal decolonization require reconnecting to land as a living being, remembering our ancestors as living teachers and rediscovering the self as a web of relationships. The whole notion that we are separate individuals motivated by rational self interest is as obsolete with the vision of progress that assumes perpetual growth at all costs.

It’s time to step into a new human story that understands we are all relations and do what is right to restore balance on the earth. In this way we have the chance to rediscover our own innate indigeneity and reclaim the sacred in every aspect of life. Our older brothers and sisters of the original nations who have retained this memory have vital keys to the viability of our species and they need our support more urgently than ever.

Shifting Climate Funding

A rapidly growing body of scientific research confirms that Indigenous Peoples are the most effective stewards of their forests and the massive stores of carbon and biodiversity within them. Despite clear effectiveness, Indigenous-led climate solutions remain severely underfunded, while speculative high-tech solutions dominate climate finance. International aid specifically to support Indigenous land tenure and forest management averaged only $270 million per year in the past decade. That’s not a typo: a few hundred million—which is less than 1% of worldwide climate finance. Meanwhile, early-stage investment in carbon removal startups in the US alone topped $1.2 billion in a single year (2023). The world is literally scrambling to bankroll machines to pull carbon from the sky—a last-ditch effort to undo the damage caused by, ironically, land mismanagement at the hands of fossil fueled machines.

Redirecting funding toward Indigenous land stewardship represents a crucial step toward ecological healing but it requires us to face the stark reality of our current condition as a species. The scientific reductionist approach to climate change isn’t working. Myopically focusing carbon as the one measure of climate success has failed. Despite significant investment in climate solutions, we haven’t been able to abate emissions at all. If we want any hope of a stable climate for generations to come we need to pull the hand brakes and restructure the climate movement with indigenous communities at the core.

Legal Innovations: Nature’s Personhood & Stewardship

Legally recognizing nature as a person, as successfully implemented with New Zealand’s Whanganui River, aligns Western legal structures with Indigenous relational worldviews. This legal innovation underscores the need to honor inner boundaries and self-respect within individuals, paralleling the external protection of ecosystems and natural entities.

The very idea that one person can draw a line in the sand and claim ‘ownership’ over a parcel of the earth is frankly absurd and is in itself at the core of the planetary crises we face. Once we begin to recognize the problematic nature of ownership as a legal construct and start to embrace economic models centered around stewardship, we will realize that there are plenty of economic and legal structures we can leverage to incentivize the right behaviors for the restoration of earth’s living systems.

Restoring Living Systems With Sacred Economics

Charles Eisenstein, in “Sacred Economics,” proposes shifting from ownership-centric economies toward models based on stewardship and gift economies. These models emphasize community, reciprocity, and the common good rather than private extraction and profit maximization. Governments should embrace “Land Back” experiments as sandboxes for regenerative innovation, creating grant structures and innovation schemes to support:

Commons-Based Governance: Land is managed collectively with governance structures that ensure community benefit, long-term ecological health, and shared responsibility, as exemplified by community land trusts or the commons model historically used by Indigenous societies.

Regenerative Incentives: Economic frameworks reward ecological restoration, biodiversity enhancement, and regenerative agriculture, creating financial incentives for beneficial behaviors rather than exploiting finite resources for short-term profit.

Access Rights and Stewardship Contracts: Rather than absolute property rights, individuals or groups hold rights to steward and responsibly utilize the land, maintaining its ecological integrity and community value. These rights can be conditional, based on demonstrating positive outcomes like increased biodiversity or improved soil health.

Ecological Payments and Value Recognition: Monetary systems reward individuals and communities for measurable ecological improvements. These could involve ecosystem services payments for carbon sequestration, water purification, or soil restoration, aligning individual economic incentives with planetary health.

By integrating these innovative economic and legal concepts into our societal frameworks, we can more effectively support Indigenous-led stewardship and cultivate a profound and necessary transformation in our relationship with the Earth.

Decolonizing the Psyche

The Land Back movement offers a profound metaphor for inner healing—addressing the colonial mindset embedded within our psyches. Western societies, constructed on stolen land and violence, perpetuate internalized values of extraction, domination, and disconnection. This can be seen in everything from the way we deal with childbirth, the way we raise and educate our children and the way to we treat our infirm and elderly.

This colonization of the mind is not merely philosophical—it emanates from every aspect of life. It is the voice that tells you that rest must be earned. That your worth is measured by productivity. That land is property. That time is linear and money is scarce. It is the schooling system that rewards obedience over creativity. It is the deep shame around aging, menstruation, and death. It is the way we have learned to fear slowness, silence, and not knowing. It is the belief that you are separate—from the land, from each other, from your ancestors.

It is also the systemic eradication of ancient and Indigenous wisdom, the erasure of ancestral memory, the standardization of beauty, intelligence, and success through a white, male, able-bodied lens. It is the suppression of grief, the medicalization of spiritual crisis, the hyper-rationalization of the sacred. It is the concrete box around the child’s curiosity, the cell wall built around the imagination. These are not just personal pathologies; they are symptoms of a culture that has severed itself from the Earth.

To truly restore ecological balance, individuals must undergo a parallel process of internal decolonization—one that reclaims joy as resistance, reestablishes intimacy with the land, remembers the body as a sacred vessel, and restores kinship as the foundation of belonging. It means unlearning the mythology of superiority and relearning how to listen, grieve, praise, and care again. It means recognizing that the restoration of the planet begins with the restoration of the soul amidst an increasingly fragile and unstable moral society.

A Societal Crossroads: Moral and Ecological Collapse

Today, alongside climate and ecological crises, we witness a profound moral collapse—evidenced by rampant gun violence, widespread mental health crises, rising obesity rates, and increasing isolation. These symptoms reflect a deep societal malaise stemming from systemic disconnection, inequality, and disempowerment.

Returning lands to Indigenous peoples offers an unprecedented opportunity to access diverse ancestral wisdom rooted in sustainable community living. Indigenous-led stewardship embodies the diversity, resilience, and relational approaches that we urgently need to navigate complex societal and ecological challenges, contrasting sharply with monolithic, scientific reductionist paradigms that are so clearly failing us today.

Indigenous Communities: Flywheels of Social Innovation

By giving land back to Indigenous people we have not only the opportunity to right the wrongs of our ancestors but also to catalyze a sandbox of innovation for approaches to governance and societal care for generations to come. Amidst the backdrop of a collapsing moral society, we should recognize that giving land back to its rightful stewards provides profound opportunities for reimagining our education systems, justice systems, healthcare institutions, and the way we care care for vulnerable people and the elderly.

Education: Māori "Kaupapa Māori" curricula integrate cultural heritage, language, and community wisdom, grounding education in lived experiences and intergenerational teachings.

Justice: Navajo "Peacemaking" emphasizes healing and community reconciliation rather than punitive incarceration, fostering accountability and reducing recidivism. When acts of violence are perpetuated within the community they call together a talking circle to give chance for both victim and perpetrator to be witnessed and to be held accountable amongst elders, youth and peers.

Healthcare: Alaska’s Southcentral Foundation's "Nuka System of Care" integrates holistic wellness, relational care, and traditional practices, significantly improving health outcomes compared to a traditional western approach.

Mental Health: In Māori, autism is sometimes described as "takiwātanga"—meaning "in their own time and space," acknowledging the unique relational and temporal rhythms of the individual. Such perspectives emphasize inclusion, relational healing, and spiritual wholeness, offering radically compassionate alternatives to the stigmatizing frameworks of Western psychiatry.

Caring for the Vulnerable: Coast Salish traditions prioritize communal care for elders, fostering active engagement and intergenerational support through Elders-in-Residence programs.

Implementing Land Restoration: Criteria and Impact

A systematic approach to returning land to Indigenous stewardship should begin with publicly-owned lands historically inhabited by Indigenous communities. Criteria for such returns could include:

Historical Indigenous habitation and cultural significance.

Current public ownership

Ecological importance for biodiversity and water cycles

Proximity and relevance to existing Indigenous communities

In the U.S. alone, roughly 640 million acres (about 28% of total land) is federally owned, much historically Indigenous-held. If even 25% (160 million acres) were systematically returned, the carbon sequestration, ecological regeneration, and social justice impacts would profoundly bolster national commitments under the Paris Agreement and significantly contribute toward achieving the global 30x30 conservation target.

A Journey Toward Wholeness

Land Back isn’t just a political idea—it’s a spiritual and civilizational turning point. It asks us to remember what we’ve forgotten: that land is not a commodity, that wealth is not held in bank accounts, and that progress does not mean domination. It asks us to feel the grief of what was stolen and the possibility of what can still be healed.

It’s not enough to swap out fossil fuels for clean energy while leaving the extractive mindset entrenched in the soil of our mind. The deeper work is relational. It’s about repairing the broken agreements between people and place, between the past and the future, between our minds and our hearts. Returning land isn’t about loss—it’s about returning to right relationship.

Indigenous communities have carried the memory of this relationship through genocide, displacement, and erasure. Despite all this, they carry forgiveness and a desire for wholeness and harmony. In their languages, ceremonies, and practices are blueprints for another way of living—one where power is relational, time is cyclical, and beauty is found in belonging. To support Land Back is to say: we believe in the wisdom of those who remember, and we’re willing to lay down our illusions to help regenerate life.

This moment in history invites us to take a stand—not just for the climate, but for the soul of our species. Not just for justice, but for joy. Let Land Back be the beginning of that stand. A chance to turn toward the Earth with reverence, to turn toward one another with humility, and to turn toward the future with a fierce, loving commitment to wholeness.